MARÍA FLORENCIA BLANCO ESMORIS

La Matanza, Buenos Aires, Argentina

I woke up, changed, and my partner made mate[1]. I looked at my cell phone and I had at least 18 new e-mails. The routine began. The transmutation of the house that was part of the beginning of this physical isolation experience in Argentina started to produce other stabilities, or at least it is a way to overcome this major event by building micro-stabilities. Our home, for many of us, became a burdensome place that at moments seemed strange to us. Perhaps because we know it deeply, or perhaps because we have learned everything that we do not like about it. Ironically, the length of time spent in our houses caused a variety of sensations in our bodies, and strangeness is one of those experiences relating to the length of physical isolation, at least in the metropolitan area of Buenos Aires.

When some of us look out the window, we imagine our lives outside; we even imagine others lives in the street. I do not go to the balcony anymore.

Cloudy days begin to be the rule as leaves accumulate on the sidewalk. Autumn is slowly coming in Argentina. In these one-hundred plus days of isolation, the time spent at home has put the details of our dwelling and our living practices into sharp focus. We do not seem to be obsessed with the use of alcohol gel anymore. All the while, my days slip through my hands between emails, news, zooms and some relaxed chatting with friends. I talk to people in settlements and slums in the province of Buenos Aires and they tell me that they have run out of powdered milk and that they cannot meet the demand for food. The prolongation of the quarantine measures feels like an immense cold that ravages the body and one’s hopes. However, collective action is emerging to address such inequalities. The governments (national, provincial, and municipal) try to collaborate with organisations that carry out their own aid actions collaborate. It is true that the prolonged physical isolation has revealed the fragilities of domestic life and the limits of a physical isolation that becomes more and more overwhelming and exhausting.

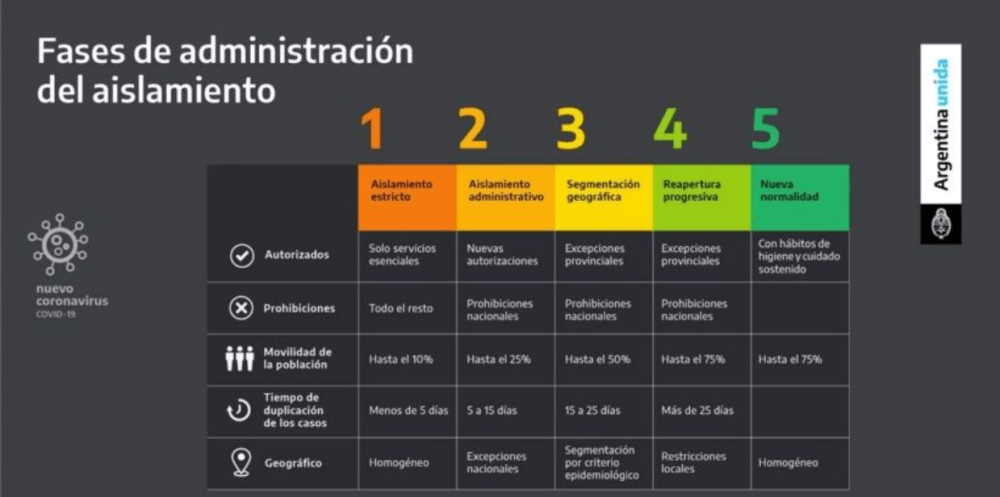

Image 1. “Isolation management phases” (own translation). Source: Gobierno Argentino.

As I wonder how people look at and divide up the world according to their perceptions, I get dressed to help with a municipal delivery of supplies and food bags to families in need, whether for nutritional needs or educational materials for their children . At the same time, colleagues bombard me with messages from WhatsApp about bureaucratic issues -such as updating forms, uploading videos- at University, but I choose not to respond and to fully focus on what I am doing: face-to-face assistance. In the midst of all this, the beginning of isolation seems far away. That time when we tried to frame the experience in a positive light, feels even more distant when now a large part of the population cannot manage to cover their daily needs.

Image 2. Quietness in Ramos Mejía (La Matanza). Photograph by the author

It is true that in Argentina we are going through this period differently, depending on where one lives. The most populated areas of the country continue in phase 3, according to mandate of the local scale. This phase is called ‘Geographical Segmentation’. That is to say, at a national level the state is diving up those geographical areas that can progressively move out of preventive and compulsory isolation (ASPO).

Within their homes, many people have reached their limits, and do not even wish to talk to others. The excessive demand for attention, and the constant attachment to screens has become unpleasant. In different groups of metropolitan middle classes, the productivity paradigm clashes with the unequal dynamics of care and domestic organisation. In the meantime, some sectors survive on the basis of a collective organization that is no longer able to cope, and the presence of the escape-valves of the State with programmes that have some degree of complexity in their implementation like the Emergency Family Income (Ingreso Familiar de Emergencia -IFE) from the ANSES agency[2]. Certainly, despite their efforts, the State – municipal, provincial, and national – cannot address equally to the entire population. Local leaderships manage resources and assets that every day reduce their supply in the face of an ever-increasing demand.

People still do not meet to drink mate, there are no meetings, and the face mask is now part of the uniform together with the physical distance.

Autumn announces its arrival and dengue fever still concerns the inhabitants in the metropolitan area of Buenos Aires where more and more cases are being detected[3]. Many of us are disenchanted with our homes meanwhile the uncertainties about the present and future continue. Inequality continues to knock on people’s doors, social decay is also becoming a reality with each passing day of this ASPO. Now, almost 100 days since day one of the ASPO was implemented in the Metropolitan Area of Buenos Aires, we have returned to phase 1. Amongst those who hope to escape from the cities to look for a sort of ‘retreat’, there are also those who instead have to make their houses a habitable place. In this ever persistent and unequal context, how can we turn uncertainty into a project, and utopia into hope?

This context also brought a number of signs of solidarity and collective work even in places where State aid does not reach. Making utopia apprehensible implies building bridges of action and mutual understanding. It is therefore a matter of looking at the experiences and responses of people´s organizations, of understanding the world from new frameworks of communication and dialogue, and of comprehending the need for a State that reaches all people. An initiative that, as a project, must include the hopes of the entire population.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

María Florencia Blanco Esmoris is a sociologist (IDAES-UNSAM) and a Research Fellow of The National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET) in the Centre for Social Research (CIS-CONICET/IDES), Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Featured Image: Raising awareness in Ramos Mejía (La Matanza). Municipal campaign: “Quedate en casa. No te contagies”. Photograph by the author

[1] Mate is a popular beverage in most South American countries: Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay and southern Brazil. It is made using leaves and small branches of the yerba mate plant, which are soaked in hot water to make mate or in cold water to make tereré. The leaves soaked in water are put in a pot, called porongo, and are drunk with a bombilla (special straw with a filter). In Argentina, the mate is part of the daily life of many people, it is shared in a round and there is always someone in charge of priming and passing the drink to the whole round. More details at: https://medanthucl.com/2020/04/16/another-day-in-quarantine-the-transmutation-of-the-house/

[2] “In the framework of the health emergency, the National Government established an Emergency Family Income (IFE) for informal workers and single-income earners in the first categories” (own translation). Source: https://www.anses.gob.ar/ingreso-familiar-de-emergencia .

[3] We have dengue fever in Argentina at least since 1998 but in 2016 we have a significant outbreak in the country. Back then the register the cases of contagion where allocated in Misiones, Formosa, Salta and Jujuy (Northwestern Argentina). The thing is that this March 2020 native cases of dengue fever where registered in the City of Buenos Aires and in Buenos Aires Province -where a third of Argentina’s population lives-. More details at: https://medanthucl.com/2020/04/16/another-day-in-quarantine-the-transmutation-of-the-house/

Download a PDF of the article: